Stirring The Pot

I’ve written before about the tension between artistic expression and the sometimes opaque broadcasting regulations that exist in the United Kingdom. On that occasion, the regulator — Ofcom — managed to tie itself in knots over the acceptability on a lunchtime broadcast of moaning noises in an otherwise instrumental dance track from what is now 30 years ago.

Well, last week they did it again. Over potentially racist language in an otherwise avowedly anti-racist song and which has been played on the radio without issue for much of the almost 50 years since its release and hit single status. And just like before it has managed to get people’s dander well and truly up.

The track in question is Melting Pot as recorded by Blue Mink, a group founded by the American keyboardist Roger Coulam and which during its short existence became one of the major platforms for the highly-regarded songwriting duo of Roger Cook and Roger Greenaway. The song was their first, arguably most famous, hit and reached Number 3 in the very first week of January 1970.

Melting Pot is an uplifting, soulful, and on the face of it a quite inspiring hippy anthem. A plea for racial and religious harmony and espousing the noble belief that we are ultimately all as one as members of the human race and should interact with each other on that basis at all times. And you will know it the moment you hear it, just as everyone recognises Blue Mink’s “other” hit single Banner Man for the same reason.

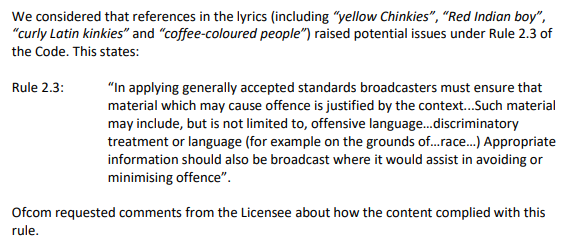

So how and why is this anthem of peace and love so problematic? Well, it is a truth that is hard to ignore. The verses themselves may well be an ode to racial togetherness, but those races are represented in terms shall we say very much of their age. Written in all innocence by two white men 50 years ago but which don’t quite pass muster in our more linguistically sensitive modern times. And all it took for this to come to the fore once more was for one person to hear it on the radio and decide to take issue with it at regulator level. At which point Ofcom were obliged to pay it some attention.

So let’s dive in and see how the “naughty words on the radio” department dealt with the matter:

As ever, it was the fact that just one person complained which raised hackles online. But this is actually irrelevant. Broadcast regulation is qualitative, not quantitative. Just as a non-issue and something not in breach of programme codes does not suddenly become so just because hundreds have written in objecting, a matter which causes a TV or Radio station to be in breach of the rules cannot be mitigated by the fact that only one person noticed, or even cared enough to complain.

All complaints to Ofcom are in the first instance assessed as to whether there is an actual code issue. And with Melting Pot and its politically incorrect lyrics having passed that particular threshold, the broadcaster was invited to offer an explanation.

Complaints about inappropriately scheduled content and which Ofcom feels minded to investigate generally result in the station in question going “oops, our error, sincere apologies” followed by an explanation of the steps they have taken to prevent a recurrence. None of which makes much of a difference as Ofcom invariably records a breach, issues a public admonishment, and moves on.

But this time Global, the owners of the Gold service, were minded to stand their ground and offered up a robust defence of the track. They noted:

- It was a song written in the 1960s and very much of its era, and should be heard in that context.

- No racial group was being referred to in a derogatory manner. It is a song of inclusivity and harmony, not hate.

- This was being played on a service devoted to music from the 60s and 70s, aimed at and consumed almost exclusively by an older audience and who were credited with the intelligence to understand.

That said, one silly pop song out of the hundreds that they regularly play was not a hill they would choose to die on. And there the defence rested:

The other thing that is important to understand here is that Ofcom doesn’t, as a general rule, decide matters of taste on a whim. They conduct extensive research as to where the tastes of the general public lie, update it on a regular basis to take account of societal change, and at all times act with reference to that research. And regrettably, they had indeed in the recent past asked a cross-section of people as to whether “chinky” is an offensive term. And the majority agreed that it was.

There is no room for nuance here, the regulators have never given themselves that discretion. It matters not whether it wasn’t so offensive in 1969. It is now in 2019 and so you probably shouldn’t use the phrase.

Why “probably”? Because as every Ofcom decision notes, broadcast regulation smashes headlong into ECHR Article 10, protecting free speech from government interference. This is resolved by allowing broadcasters an “out”. Potentially offensive content is permitted as long as it is “justified by context”.

So Ofcom asked itself whether Melting Pot was exempted by those rules. Importantly though, no context was given or available. The song was played at a time when the radio station was in presenter-free automation. A playlist service aimlessly spinning tracks. No DJ or host was present to offer any kind of context or even explain to the audience what the song meant.

OK, so what about the context offered by the nature of the service? A radio station playing “golden oldies” and largely consumed by the mature and elderly.

You will note here that mathematics is not Ofcom’s strong point. 1970 was nearly 50 years ago, not 40. Although that only serves to strengthen the point they were making that it was a hit that long ago that not everyone may remember it.

Case closed then, surely?

But here comes the fascinating part. As I mentioned above, offensive language in pop records cases are generally open and shut matters. There is one such example in the very same bulletin as the Melting Pot matter:

The radio station’s response was essentially “Yes, we messed up there, sorry” and Ofcom said “Yes, yes you did. Be better at this radio thing”.

Gold, however, got off rather more lightly.

“Resolved” is generally reserved by Ofcom for matters which are technically in breach of the rules but which were unavoidable despite all steps being taken to prevent it. Guests accidentally saying “fuck” on daytime TV for example. If you apologise immediately and show that they did this despite explicit warnings not to, then you get sent away with a regretful shrug of the shoulders.

I’ve genuinely never seen this happen in the context of an inappropriate lyric. As if there is a tacit acknowledgement that this is all a bit silly. That judging 50-year-old material through the same eyes that are expected to assess brand new productions does feel rather ludicrous. Gold took the opportunity to do the right thing by saying “perhaps we just won’t play it again”, so Ofcom, in turn, gave them an out. No slap on the wrist needed. We’ll all agree to move on.

That’s why some the more excitable posturing which appeared online in the wake of this decision was more than a little over the top. The record has not been “banned” from radio airplay. It comes attached with a warning that it has the potential to cause offence, but as long as you warn the audience of this (in the same way a TV show featuring violence might precede the broadcast with an advisory) then you will probably be OK.

In a world where vast libraries of recorded music are available online for ready consumption, it matters not that the only radio station regularly playing the song have politely decided not to do so any more. Because you can listen to it in the privacy of your own home as many times as you wish.

The full text of the judgement at times makes for some absurd reading, so I get why there was no small measure of sneering upon its release. But, as the judgement in a court challenge to an Ofcom decision once noted, their modus operandi is “anxious scrutiny”. No decision is ever made on a whim or without full justification. Ofcom took time to consider not only the content of the song but the circumstances of its airing and decided on its offensiveness with due reference to evidence-based research. That’s quite comforting in a way.